At the close of the UN Climate Summit in December 2018 in Poland, United General Secretary Antonio Guterres was so discouraged by the lackluster outcome that he told world leaders that he would admonish them to increase their urgency and ambition for climate mitigation during Climate Week in New York City (Sept. 23-27, 2019).

Guterres is not alone. Swedish teen Greta Thunberg, in her inimitable way, has inspired millions of school-age children around the world to organize and rally to demand that world leaders treat global warming at the existential crisis that more and more scientists are finding it is.

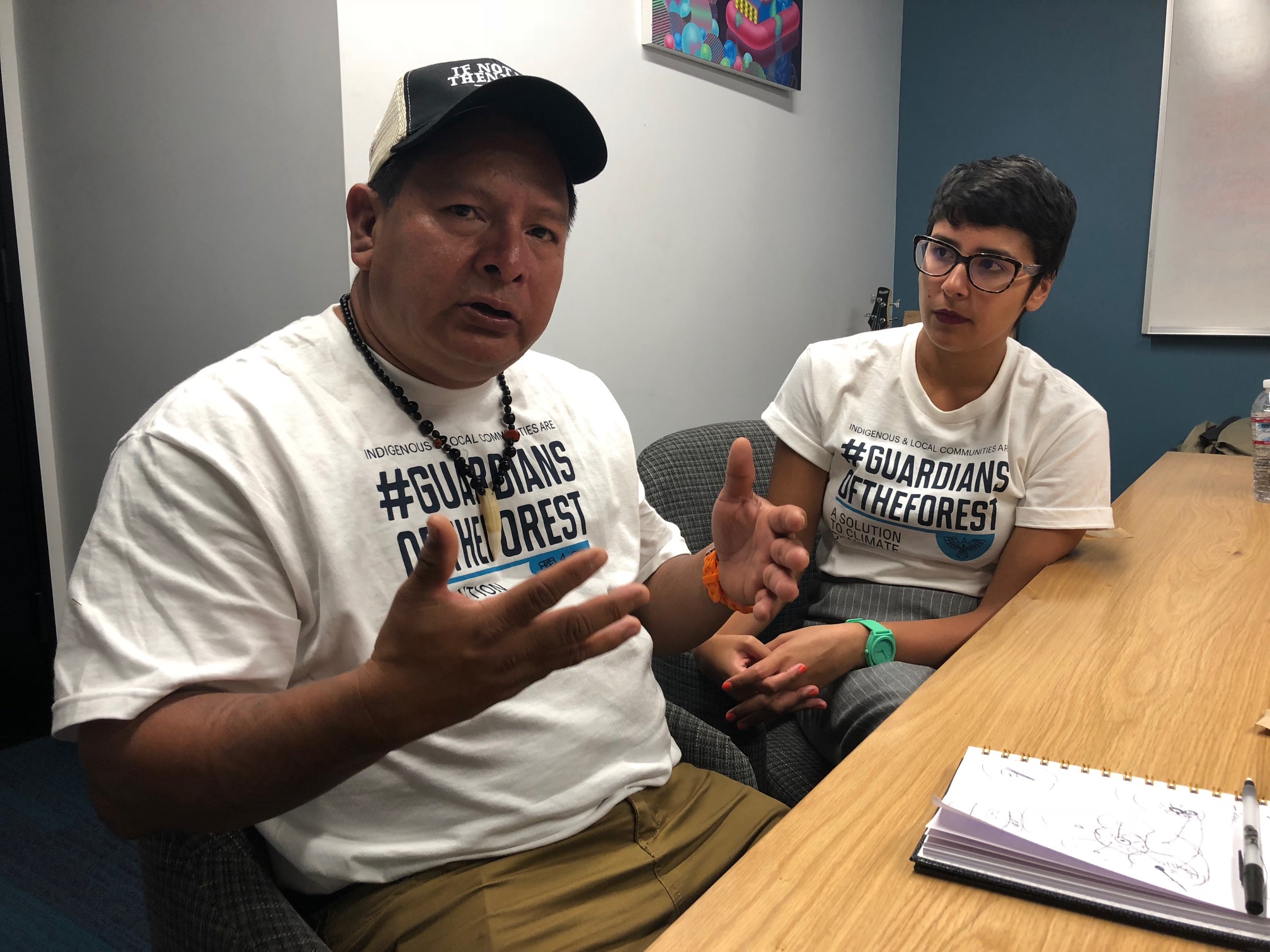

Add to that an emerging group of faith leaders — the Interfaith Rainforest Iniative (IRI) — that aims to use its moral clout and power in numbers to pressure national leaders to enact policies to slow, reverse and stop deforestation in five tropical countries, as my latest Mongabay story describes.

This kind of religious political lobbying comes with challenges and obstacles, as I explain. But here’s the goal:

“This isn’t about churches planting trees,” said Joe Corcoran, IRI program manager with UNEP, the United Nations Environment Programme. “We want to say clearly and definitively to world leaders: religious leaders take this issue of forests and climate very seriously, and they are going to be holding public officials accountable to make sure these issues are addressed.”