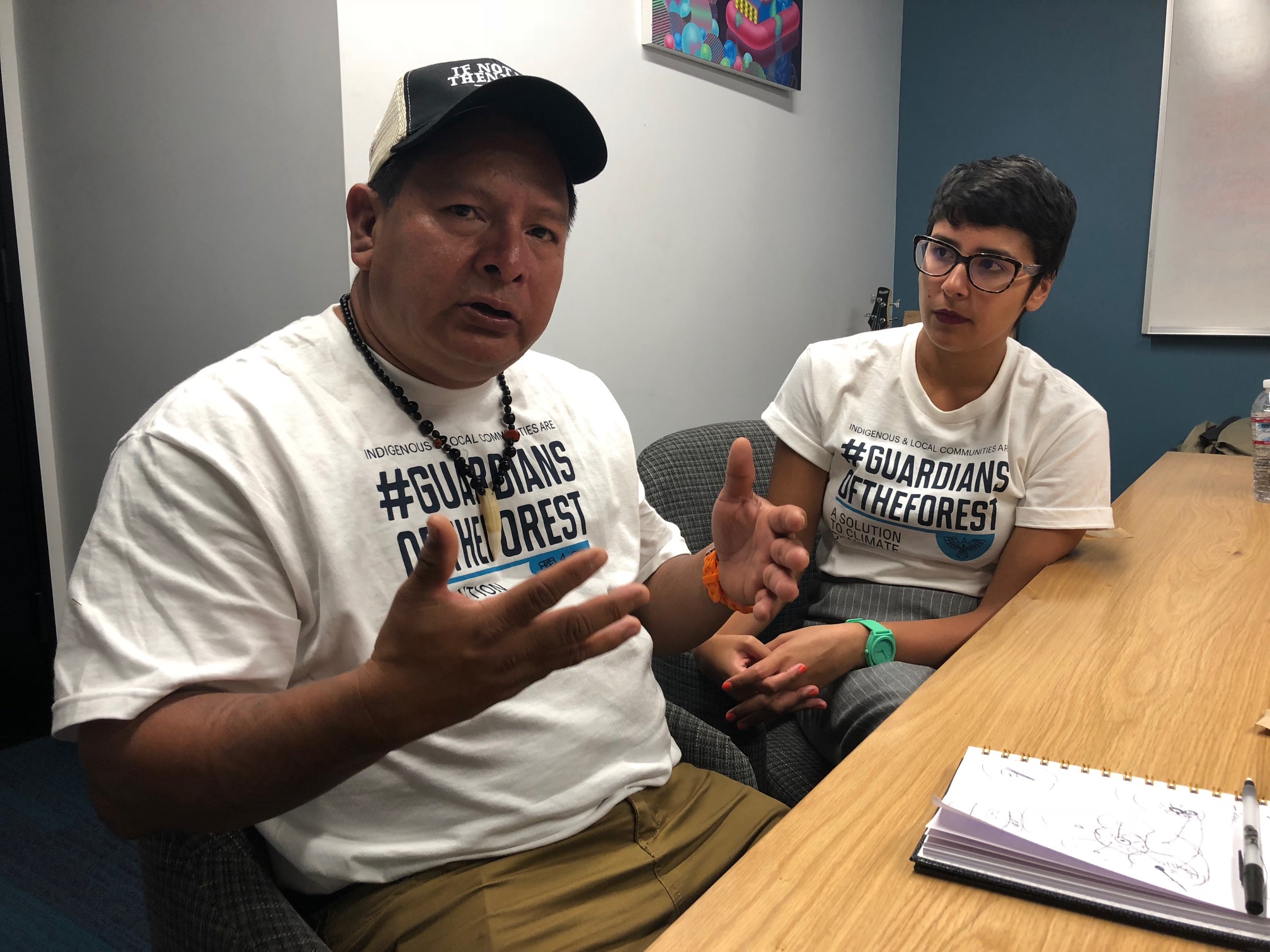

Guardians of the Forest at Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, September 2018. Photo by Joel Redman, courtesy of If Not Us Then Who.

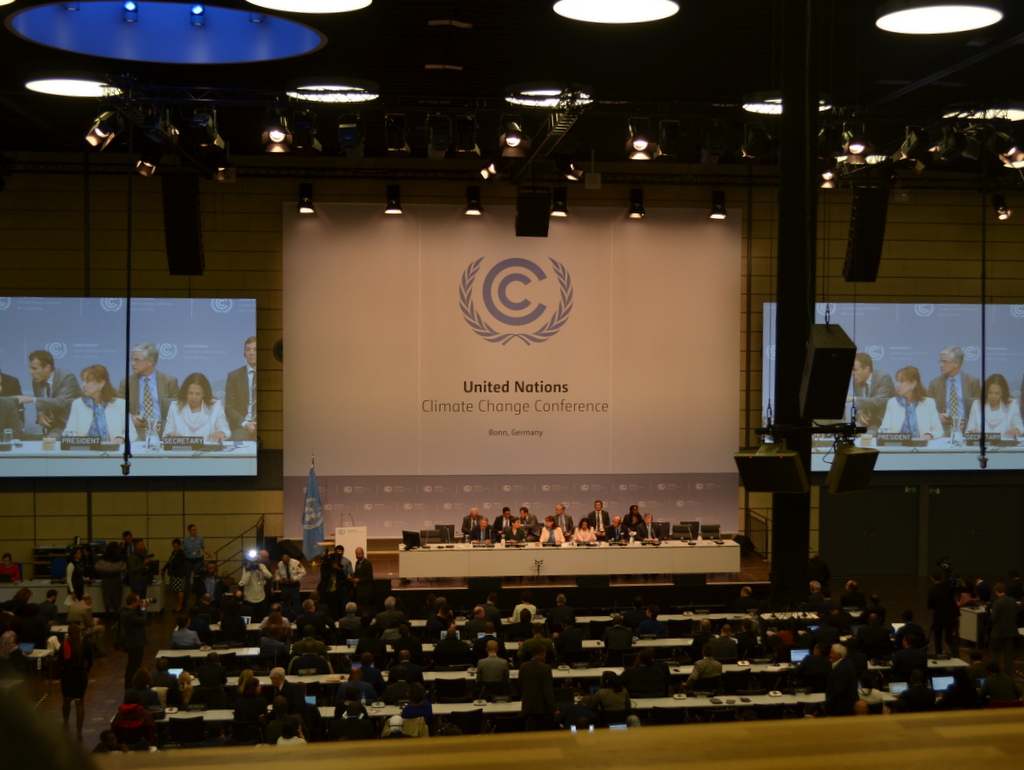

Several weeks before I flew to San Francisco ahead of Hurricane Florence to cover the Global Climate Action Summit hosted by Gov. Jerry Brown (September 12-14, 2018), I had a conference call with Mongabay special projects editor Willie Shubert and videographer/activist Paul Redman of the nonprofit group If Not Us Then Who. His group seeks to raise the visibility of indigenous peoples and their role in forest protection.

Willie had an idea for the story — ultimately, this story — and Paul had details about how I could get at it. His group was hosting a side event to the summit in which tribal leaders from around the world would meet for presentations, panel discussions and documentaries. What’s the story? I asked. They both offered ideas and themes, both general and specific. But I realized that this was one I just had to trust, trust that if I spent enough time at the side event, and spoke to enough people — along with the reading and research I would do in advance — that the story would come to me.

I spent several hours both September 13-14 at Covo, the co-working space where the side event was being held about a half mile from the Moscone Center and the main summit. Paul was there Thursday; he was tremendously helpful, lining up a trio of exceptional sources for me to interview one-on-one while I took notes during panel discussions and took in the scene. On Friday I interviewed NGOs with the Nature Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund for greater context. And little by little, I got the sense that I had witnessed something special, something important, and that I had the pieces I needed to tell the story.

This one quote by a remarkable tribal leader from Panama crystallized the theme of my story and led me to the equation around which I built my story: indigenous peoples + land title and tenue = climate mitigation:

“There is one basic principle,” Candido Mezua told Mongabay through a translator. “We cannot see the forest or nature as a tool for getting richer. That is something the indigenous people cannot do… We are contributing to climate stability, something we have been doing for centuries without being compensated one penny.”