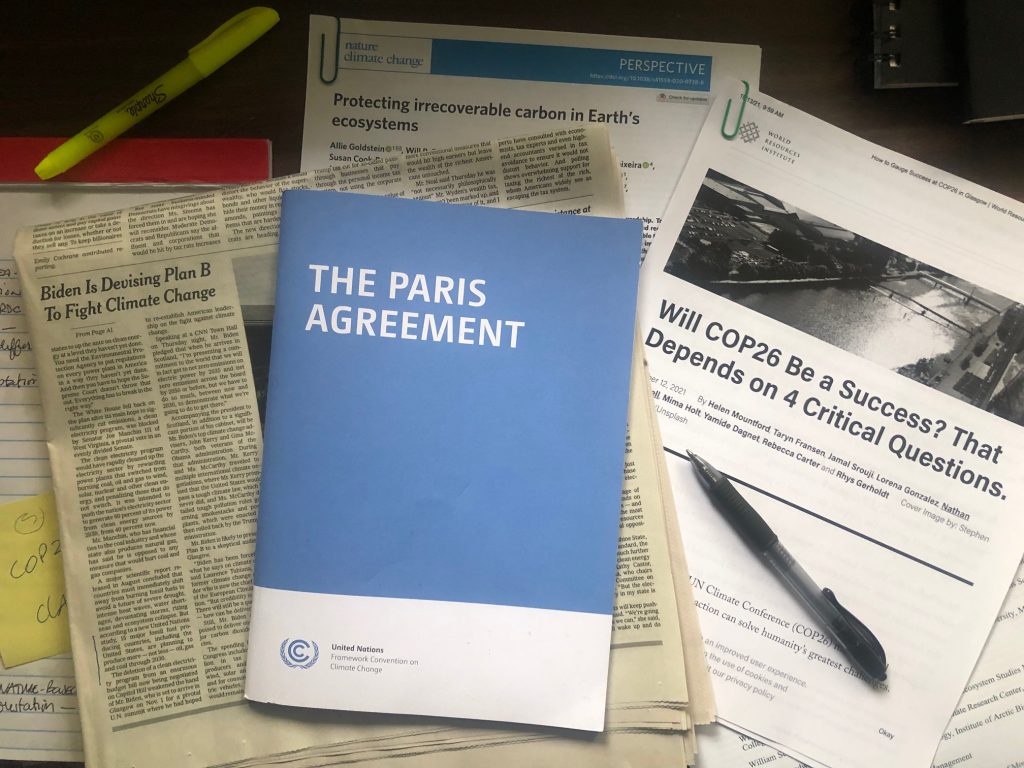

At the conclusion of every UN climate summit I’ve covered since Paris in 2015, I’ve written a story that summarizes the highlights (few) and disappointments (many) in a kind of post-COP analysis. Because of the massive global media attention COP26 drew (nearly 4,000 credentialed journalists), that story was largely written by others before I landed back in North Carolina.

Instead, with this final story from COP26, I followed an idea that came to me during my return flight home. I decided to focus on what seemed to me to be two significant positive developments from a climate summit that was declared a failure before it even started. Those two elements — one old and easily grasped, the other new and technologically futuristic — could turn out to be climate game changers in the decades ahead. That is, of course, if they receive the international support and billions in funding required to enable both to, in one case flourish, and in the other, reach proof of concept on a global scale.

Let’s be clear. The coordinated effort to save the planet by holding global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C over pre-industrial times has virtually no chance of succeeding without these efforts I write about, in combination with accelerated efforts to decarbonize industrial economies and halt deforestation and biodiversity loss in the world’s great forests. G-20 leaders have simply wasted too many decades making problems worse for any shortcuts or easy fixes to this existential climate crisis.