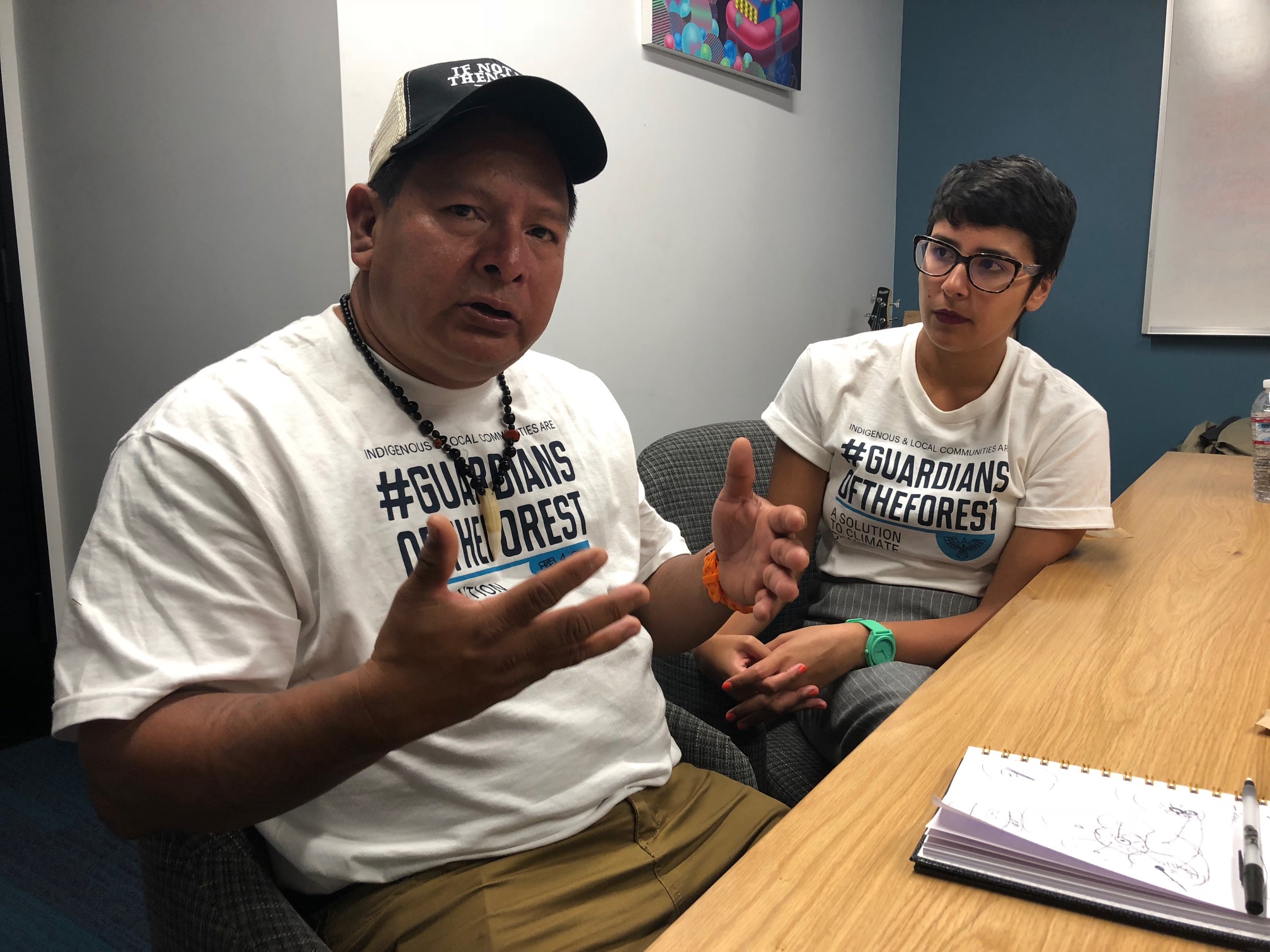

Bianca Jagger on Sunday morning, Dec. 7, in Lima, Peru, at an event connected to the UN climate talks. She is speaking to Heru Prasetyo, a climate change expert from Indonesia. Photo by Justin Catanoso.

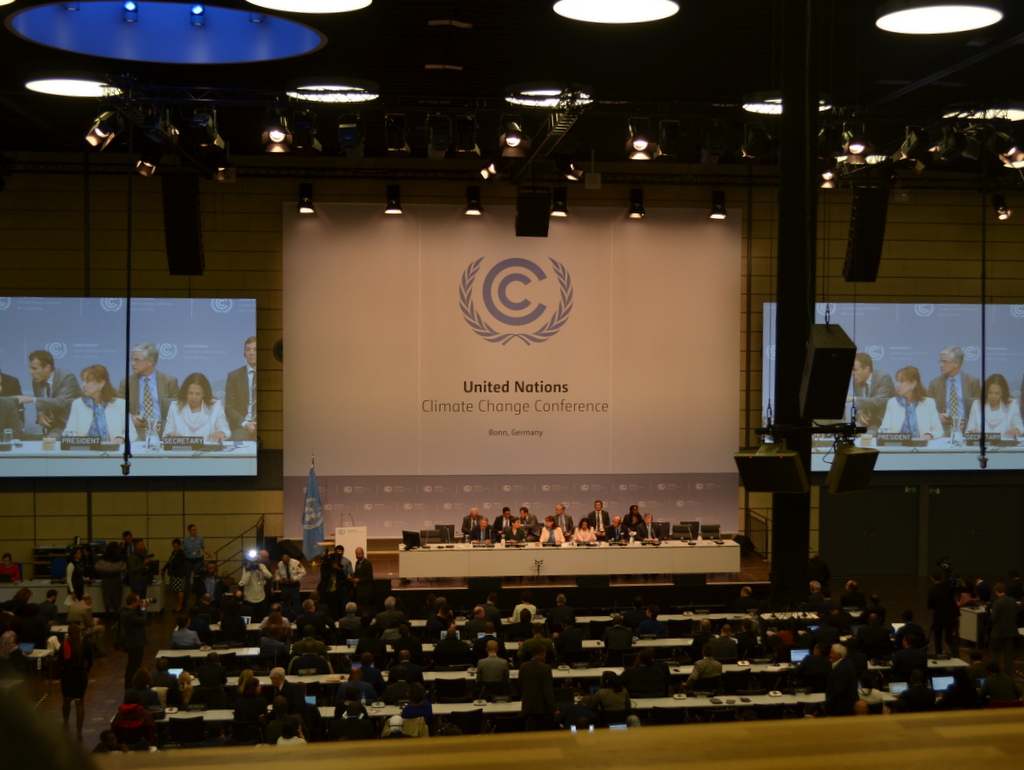

Note: I am in Lima, Peru, reporting on the COP20, the 20th annual United Nations climate negotiations. I arrived Dec. 6 and will remain through the end of the conference on Dec. 12. This is my first story.

LIMA, Peru – Whatever her youthful reputation as the wife of a world-famous rock star and glittery jet setter, Bianca Jagger has committed much of the past 30 years of her life to advancing causes associated with human rights and environmental protection in the developing world.

On Sunday morning, during a side event connected with the annual UN climate negotiations here in Lima, Peru, the 69-year-old Jagger sounded every bit the international diplomat she’s become in recent years. Delivering an impassioned 13-minute talk during a panel discussion, she spoke bluntly about the perils of climate change and the need to restore both destroyed and degraded forests as the best strategy to reduce the ongoing damage.

“Climate change will affect everyone, everywhere, in every nation, in every echelon of society, in the developing world and the developed world,” said Jagger, a native of Nicaragua and British citizen. “We will all suffer the catastrophic consequences of rising sea levels, ocean acidification, food scarcity and political unrest. But some of the most vulnerable communities in the world are bearing a disproportionate burden of the harm without having significantly contributed to the cost. This is a terrible injustice.”

Photo by Justin Catanoso

Noting that climate experts predict that 2014 will become the hottest year on record, Jagger warned: “Time is running out. Inaction will lead to severe and irreversible damage.”

In another time, in another setting, Jagger may have been the star attraction at an event such as this with fans and paparazzi swarming to bask in her celebrity. There was little of that in evidence Sunday morning during the Global Landscapes Forum held at the Westin Lima Hotel & Convention Center.

WITH A CROWD of mostly influential scientists, top environmental activists and leading figures from the United Nations, World Bank and World Wildlife Fund, Jagger arrived without fanfare as the founder of the London-based Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation. She appeared elegantly striking just the same, dressed in a full-length white wool coat with sparkling flats and leaning on a Dalmatian-spotted cane. She greeted a small knot of well wishers and quietly took her place on stage. Three other panels were taking place at the same time; Jagger’s panel – “A new climate agenda? Moving forward with adaptation-based mitigation” – attracted about 100 people.

Jagger noted that two years ago, she was appointed an ambassador to the Bonn Challenge, which aims to restore 150 million hectares (370 million acres) of degraded or deforested land around the world by 2020.

“I took on this role because I believe the objective of the Bonn Challenge is critical and more importantly, it is achievable,” she said. “Frankly, it is one of the more achievable initiatives trying to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and improve the lives of people. Achieving the Bonn Challenge goal could sequester 1 gigaton of carbon dioxide a year, which would reduce our current emissions by up to 17 percent. That is really a very important advance from a restoration program.”

Bianca Jagger, before the start of the panel discussion. Photo by Justin Catanoso

The two-day landscape forum focused largely on the underappreciated role forests play globally in slowing the rate of climate change by absorbing tons and tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually through the process of photosynthesis. Millions of acres of tropical forests around the world (which do the most work in carbon sequestration) are destroyed for agriculture, mining and extraction. The clear-cutting is often far more than is necessary and at great costs to biodiversity and the indigenous peoples who make their homes and living in such forests.

A PRIMARY GOAL of these 20th annual UN climate talks is for governmental and environmental leaders from 200 countries to draft a legally binding agreement that can be signed as a global treaty next year in Paris. Despite accords that came out of Kyoto (1997) and Copenhagen (2009), no treaty currently exists, even as the accumulating evidence of ongoing, manmade climate change continues to pile up.

“Time is running out. Inaction will lead to severe and irreversible damage.” — Bianca Jagger

While progress appears to be halting after the first of two weeks of negotiations, the Lima draft is hoped to contain an array of strategies to slow the rate of greenhouse gas emissions largely through the reduction of burning fossil fuels for energy and transportation. Such reductions are seen as vital to hold global warming below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit in the next 50 to 85 years. Beyond that point, scientists predict far worse extreme weather patterns than we now see, greater coastal erosion, more water shortages and increased food scarcity than is already cropping up around the globe.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions – the airborne layer of chemicals in the atmosphere responsible for global warming – can go beyond cutting back the extracting and burning of fossil fuels. Other strategies include the expansion of alternative energy sources, greater fuel efficiencies in transportation, as well as similar efficiencies in home and building construction and lighting and appliances.

Increasingly, as the landscape forum emphasized and as Jagger stressed in her talk, the massive preservation of existing tropical forests, and replanting ones that have been damaged and destroyed, can play a significant role — if not the most important role — in staving off catastrophic climate change.

Jagger said the United States, along with countries such as Rwanda, Costa Rica, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Guatemala have already committed to restore some 51 million hectares (126 million acres) of forests by 2020 as part of the Bonn Challenge. She lauded large-scale restoration efforts in China and Brazil, too.

“It is true that governments have not come forward to do what is necessary,” Jagger said. “It is true that we don’t have a legally binding treaty now. But if we can continue with initiatives like the Bonn Challenge, we would see a difference. Forests are essential to our future.”

Justin Catanoso is a freelance journalist based in North Carolina and director of journalism at Wake Forest University. His environmental reporting is supported in part by the Wake Forest Center for Energy, Environment and Sustainability, and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in Washington, D.C.