Top officials celebrate after the Paris Agreement was signed in December. But critics see no acceleration.

Acceleration? It depends on who you ask. That’s why the irony of this celebratory photo, taken immediately after the Paris Agreement was approved by 196 nations in mid-December, is so apparent here in Bonn, Germany, at the United Nations annual mid year climate conference.

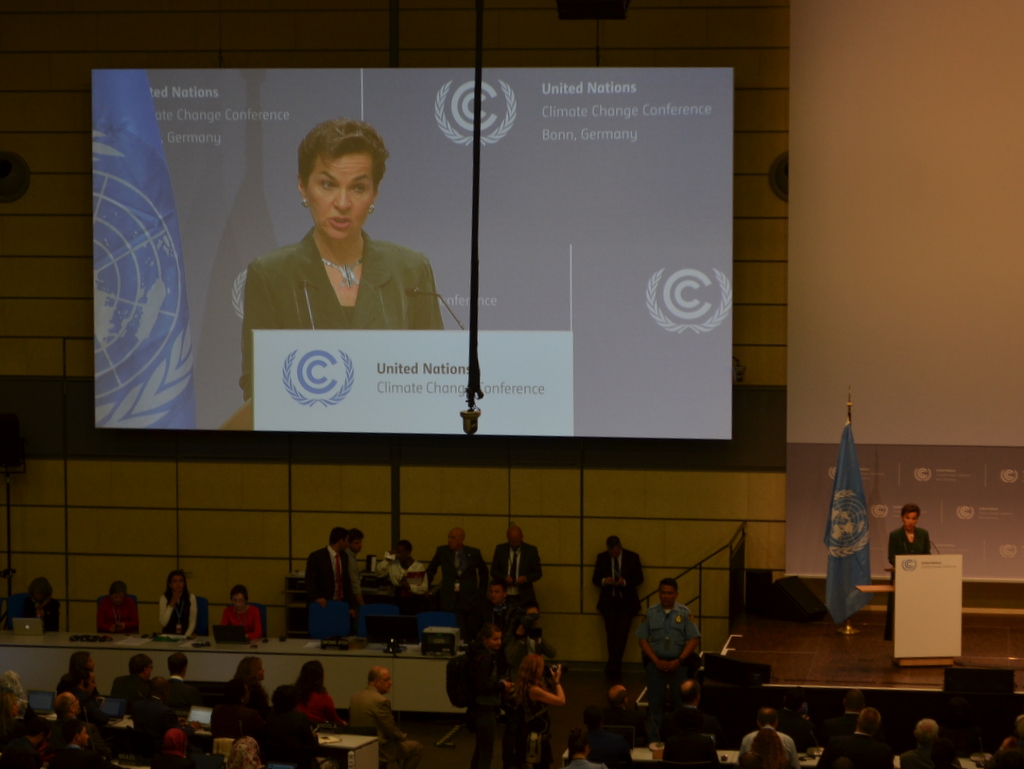

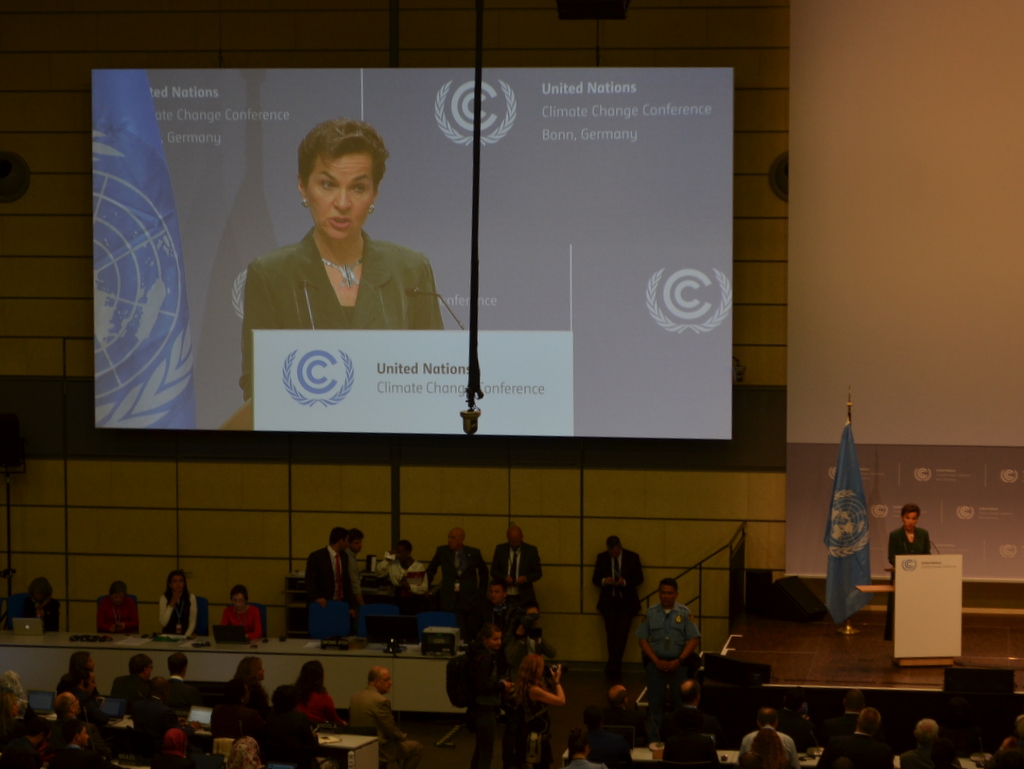

On Monday, May 16, Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), proclaimed the Paris Agreement as “a historic achievement.”

“Today marks a new era for all of us,” she declared with great hope and enthusiasm to a plenary of national leaders. “With the support of thousands of non-Party stakeholders, you were able to make the seemingly impossible possible. You have brought down the many barriers that divided you. You have opened many opportunities that now unite you.”

Christana Figueres, UNFCCC, at the opening session in Bonn

It sounds good. In many ways, it is good. Never before had virtually every nation on earth pledged to set voluntary goals to reduce their carbon emissions. They pledged also to fight deforestation and promote reforestation in vitally important tropical countries. Most critically, they pledged to hold the rise of global temperatures by 2100 to another 0.5-degree C, instead of a full 1-degree C.

The Paris Agreement got the world drunk on hope. But the buzz has worn off here in Bonn. Impatient activists and NGOs, particularly from poor, vulnerable nations now suffering the ravages of global warming, deride the lack of progress since Paris among the world’s most powerful nations and largest carbon polluters — China, the U.S., India, Russia, Japan and the EU.

They are rightfully impatient. They have already waited too long. Paris was COP21 (Conference of the Parties). Simply put, that means the first 20 UN climate summits ended in failure. Two decades of possible progress were lost to climate denial and political skittishness.

Thus, the claim in the top photo — We’re Accelerating Climate Action — looks like a lie to the critics here as it greets them each morning upon arriving at this modern conference facility made of glass and steel.

“Immediately after the UK signed the Paris Agreement, officials returned home and approved $3.3 billion in dirty energy subsidies for oil and gas companies,” said Asad Rehman with Friends of the Earth-UK. “Those subsidies should have been canceled given the Paris Agreement. We see a huge disconnect between what is said here (in Bonn) and what is happening here and at home.”

Rehman spoke at a May 18 press conference that assessed the Paris outcome and international action over the last five months. Impatience ran high among the panelists. So I posed a devil’s advocate-type question: “Global leaders in Paris agreed in December that the agreement did not go far enough. They all pledged to revise the strengthen the document in the months and years ahead. Don’t they deserve a little more time?”

“Our people are already dying,” retorted Lidy Nacil with the Asia Peoples Movement on Debt & Development, told me. “Fossil fuel projects should have been canceled right after Paris.”

Rehman added: “You must understand. It’s not just been five months. Governments have willingly failed to act for more than 20 years. The UN has called for carbon reductions in 1990. Since then, carbon emissions have increased globally by 60 percent.”

Celia Gautier with Reseau Action Climate of France said the recent French government’s ratification of the Paris Agreement “Is not not sufficient. There will not be a magic wand to  change climate action around the world that will keep temperatures around 1.5-degree C.

change climate action around the world that will keep temperatures around 1.5-degree C.

“Countries need to phase out fossil fuels now. The G8 must take the lead. But they are still reluctant to provide a road map on how the money will be raised to achieve of the goals of the agreement. Rhetoric needs to be matched with action. And we are not seeing it.”

Tamar Lawrence-Samuel, associate research director at Corporate Accountability International in Boston, said the U.S. managed to take credit as a stalwart hero of the Paris Agreement while continuing to send contradictory messages at home. No to Atlantic Ocean oil drilling and the XL Pipeline; yes to increased oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and the Arctic.

“The United States continues to pollute itself between a rock and a hard place,” she said.

In covering this grim and dire story of international climate change since 2013, I have tried to remain open to the possibilities that nations, states, cities, faith groups led by Pope Francis and other faith leaders, and innovators funded by Bill Gates and Elon Musk can and will bring about the change necessary to stave off the worst effects of climate change.

What choice do we have but to cling to hope?

Yet I am reminded every day in Bonn that optimism comes with a price and the expectation of uncompromising political will. And that despite the Paris Agreement being exactly what Christiana Figueres hailed — “a historic achievement ” — turning rhetoric into meaningful action remains a complex and daunting task.

The UN meeting here in Bonn runs through May 26.

My reporting in Bonn is being sponsored by funds provided by Wake Forest University, where I am a professor of journalism and director of the journalism program.